Apartments – Are We Repeating Past Mistakes?

21

JULY 2021

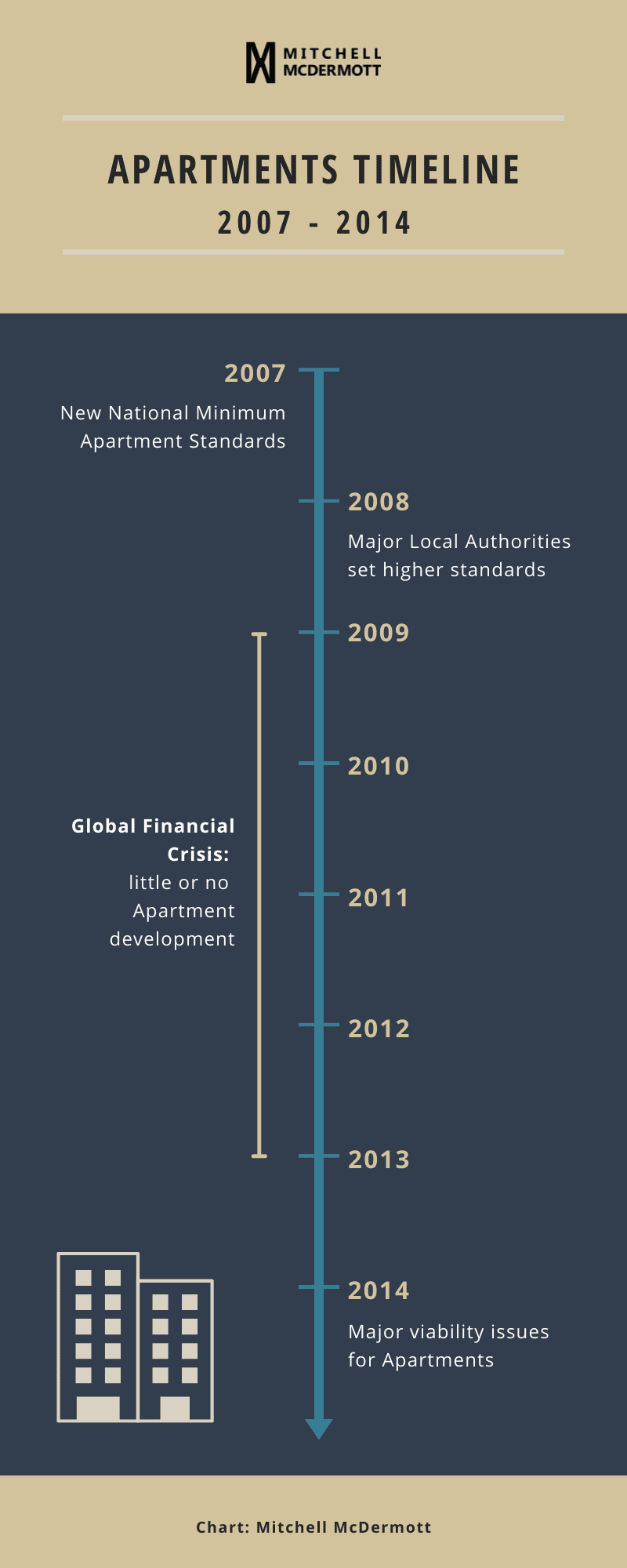

Apartment development in Ireland has had a chequered history. Fuelled by readily available debt, inflated prices and eager novice landlords, it flourished during the boom. Responding to public cries for better standards including the abolition of bedsits and the end of shoe-box apartments, the Department of Housing (DoH) put national minimum standards in place in 2007.

Unintended Consequences

Encouraged to increase their minimum requirements for apartments, many local authorities actually imposed higher standards, effectively making apartments unviable. It did not matter in any case, as the country was in the grip of the global financial crisis but as Ireland started to recover in 2012/13, Developers (read Receivers) started to look again at apartment development and found that they were unable to make them financially viable. Over the following years, favourable changes were made to planning guidelines and apartment standards that unlocked development. However, over the past two years, there has been a gradual dismantling of the work that had begun to bear fruit. Did we get it right before, or are we about to repeat the mistakes that were made in 2008?

In 2013/4, there was concern over the threat to FDI jobs and a lot of hand-wringing about the need to solve the apartment development dilemma. An analysis by Property Industry Ireland (PII) of the 2008 standards introduced by Local Authorities, revealed a 20% increase to the cost of delivering an apartment, while not adding any significant value to the occupier. Another major impediment to development at this time was a lack of finance.

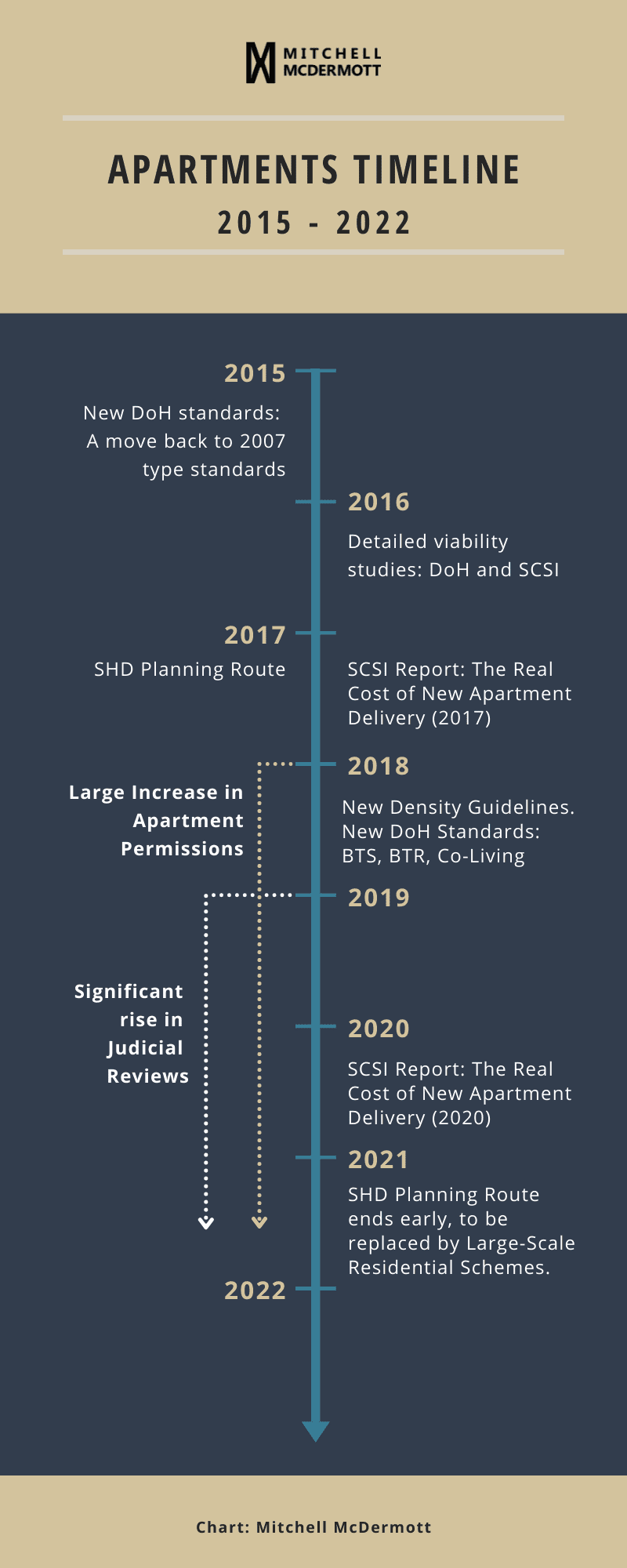

Following a review of the standards, the Department of Housing, in December 2015 published national mandatory standards which could not be altered by local authorities. Several in-depth reviews were underway at the time, including one by the SCSI. The DoH issued updated guidelines in October 2016, introducing the concept of Build to Rent (BTR).

Hard Data

In 2017, the SCSI published ‘The Real Costs of New Apartment Delivery’, an evidenced-based report which presented empirical data and shed light on many of the real issues at hand. Important decisions have previously been made without the use of hard data relying instead on public sentiment and the political mood. The report also addressed issues identified with planning permission and sustainable living.

2017 saw the introduction of the so-called ‘fast-track’ Strategic Housing Development (SHD) planning application route and, in 2018, the Urban Development and Building Height Guidelines were published, effectively removing height caps. These changes, combined with the influx of international finance, drove new apartment planning applications and subsequently the start of new development.

Long Lead Times

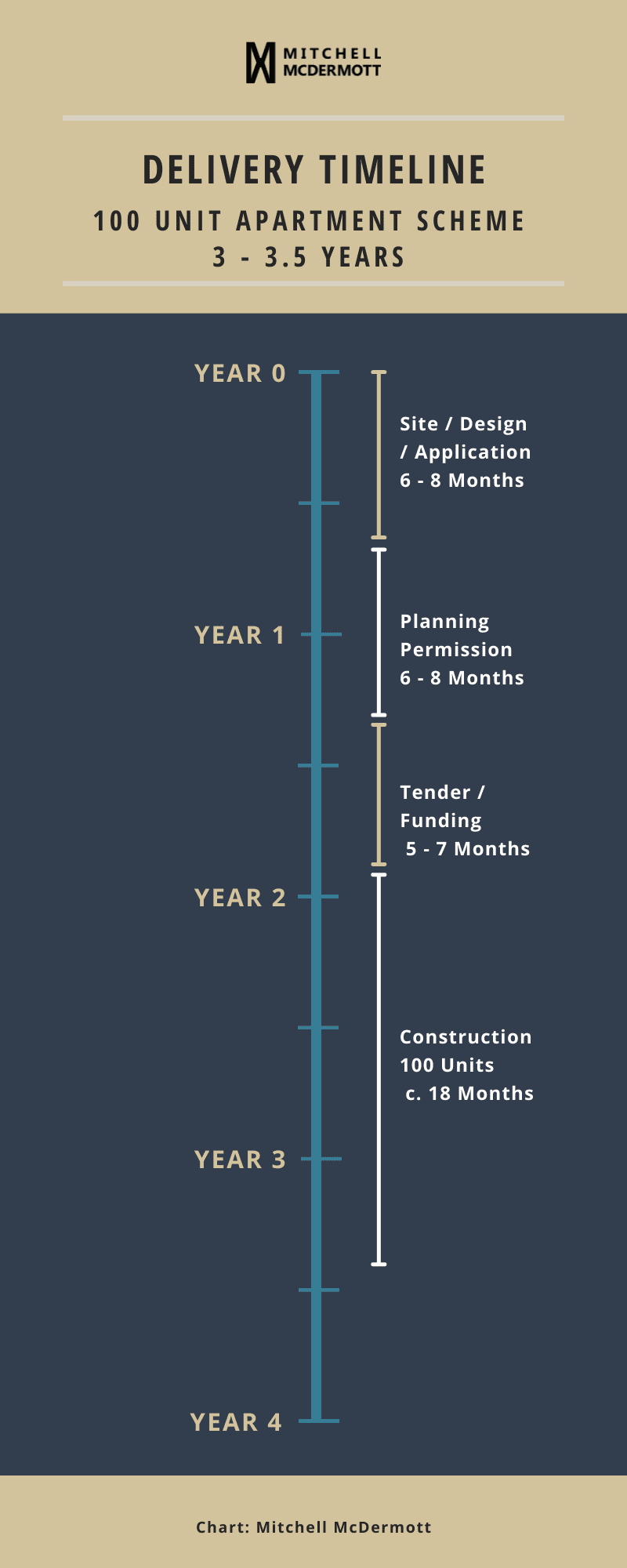

Apartment development is complex. From site purchase to turning the key in the front door, there is a significant lag time. Changes in planning, financing, and design, for example, can affect this process and delay the arrival of new homes. Typically, a 100-unit apartment scheme (which is usually capable of phasing) with planning permission granted and finance in place, can take 17-23 months to get started on site, and if you allow another 18 months for construction, the overall process can take 3 to 3.5 years. In this risky game of snakes and ladders, with its many hurdles and setbacks, the delivery of new homes can be adversely affected.

In 2020, the SCSI published ‘The Real Costs of New Apartment Delivery’ which charted the rise in apartment development by examining the data from 9,500 apartments. The data revealed that BTR schemes were more viable than the Build to Sell (BTS) projects and, also highlighted the affordability issues for potential homeowners.

2020 saw a stark increase in the amount of planning permissions being quashed through the Judicial Reviews taken against An Bord Pleanála. In January 2021, Mitchell McDermott examined all planning permissions issued under the SHD process and the research established that there had been a ten-fold increase in JR’s taken between 2019 and 2020. Further analysis in June 2021, revealed that in the first six months of 2021, a third of planning permissions were refused by ABP, a third were under judicial review with only a third successfully granted permission. Of all Judicial Reviews to date, 92% of approved planning permissions have been quashed by the courts.

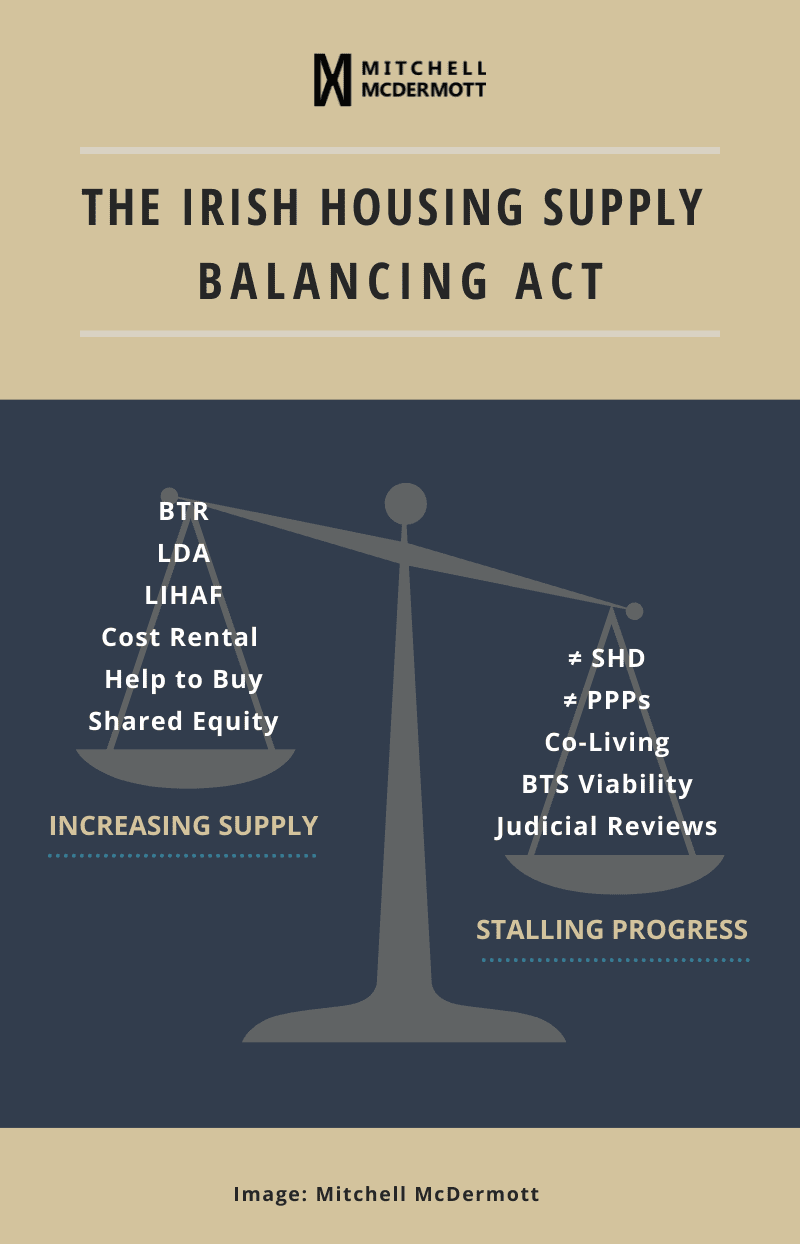

In 2020, on the back of negative press, Co-Living which had been introduced in 2018 was banned by the Minister for Housing. This type of development was only ever going to make up a very small percentage of the housing stock but would have provided much-needed homes. Furthermore, after political pressure, a major PPP scheme, which was due to deliver 850 homes was overturned by councillors. This fed into a notional premise of only having public housing on public land. International finance, which funds the majority of new apartment schemes, and helped Ireland begin the journey to deliver new homes, is often referred to in pejorative terms. While we need to protect the right to home ownership, we also need to be aware of the role international funds play in the delivery of our other tenure typologies.

A public-private divide has grown over the course of the last couple of years. Some political parties argue that local authorities should provide direct development and, while this is a reasonable position, it fails to recognise that it is the same contractors who are building the units in either case. Local Authorities do not employ hundreds of brickies or plasterers. What we are talking about here is a different procurement method. However, the cost of this public procurement does need to be examined.

It was abruptly announced this month that the SHD planning route, which was brought in to fast-track a sluggish planning permission process, and which was due to end in February 2022, would cease this October. It is to be replaced by a two-step, time-bound process for large-scale developments, which seeks to restore the role of local authorities. In 2020, we have seen and heard a litany of negative press around BTR. Will this be the next form of tenure to be terminated?

However, are we now starting to embark upon similar knee-jerk reactions? We have banned Co-Living, abruptly ended the SHD route without a known replacement, cancelled major PPP schemes, increased Part V overnight along with other non-performances, not to mention the treacherous JR icebergs that have not been dealt with, which are adding serious delays to our otherwise 3-year crossing.

Final Thoughts

In conclusion, there are positive incoming changes in the upcoming Affordable Housing Bill, including Cost Rental, the Land Development Agency (LDA) and Shared Equity. These are welcome and will hopefully increase output and assist with affordability. There is a lot of noise around these too though. Continuing the nautical metaphor, we need a rather deaf captain. One who only uses maps and instruments to chart the course, rather than reacting to the clamouring at the wheelhouse door.

The JR issue, although blamed on the SHD process, is more likely due to the removal of height caps and denser schemes getting permission from ABP. The introduction of the new Large-Scale Residential Development (LSRD) system will hopefully help the planning system but, if people have another option to stop an unwanted development, they will most likely use it. The JR process must be addressed immediately (not within the 18 months as stated by the Government in June) so that it is not used as an appeal court to ABP.

To achieve 35-40,000 units a year, we need to be firing on all housing cylinders: BTS Apartments, 3-bed semis for home ownership, BTR, Social, Affordable, Cost Rental, PPP’s AHB’s, direct public building programmes and one-off homes.

Housing, in particular medium to high density housing, is complex. Any potential changes need to be fully thought through before implementation. We look forward to the release of the ‘Housing for All’ strategy later this month. It will hopefully provide a sound basis for addressing some of the current and past issues and take a long term view on addressing our housing shortage.

Paul Mitchell